Spoilers for INDIKA abound.

Providence

Religion is a subject that is not often explored in video games. It is often enough invoked; deities are name-checked and depicted in games from Final Fantasy to God of War to Age of Mythology, and some games even invent fictional religions to build out world lore (World of WarCraft, Mass Effect) or to motivate factional allegiances (Dead Space, Silent Hill). But games rarely explore the mechanisms of religious ritual or examine the psychology of belief.

Despite this, video games are specifically suited to explore such subjects. They cast players as beings — subjects — within worlds that inarguably have gods. Worlds that were intelligently designed, in which beings that are external to and transcend the simulation have a plan for its characters and intervene in order to give meaning to characters’ “lives”.

There is an under-discussed element inherent in designed play that we all recognize, though I have never seen it named outright. I playfully call it instrumental providence. It is the recognition that, as the main character of a game, the game world is designed specifically for our benefit, to give us every affordance and resource we need to complete our journey. This is why something that would be existentially threatening in real life — like the exit to a cave collapsing behind us, sealing us inside — is met with relief in a video game. If a passage is sealed, it does not mean that we are trapped, the game has signaled to us that everything we need to progress lies in front of us. The possibility space has narrowed such that we no longer have to keep the previous rooms and passages in our active memory, we can have faith that the remaining areas accessible to us will contain everything that is needed to survive and thrive; a new exit will be revealed, one that points us toward grander adventure and greater reward.

This is an act of faith in the benevolence of a guiding storyteller, at least in linear, avatar-based narrative games. This has been obvious from very early on; Mario’s first platforming adventure only scrolled in one direction, acting as an implicit promise that Mario’s goals would always be to the right of the present position and never off-screen to the left. The rare narrative games that broke this faith (such as the early Sierra adventures in which it was possible to miss crucial items and end up in an unwinnable position) did so explicitly as a joke, subtly remarking how funny it would be for a storytelling system to be ambivalent to the success of its protagonist. The inherent abstractness of early video games makes this instrumental providence wholly unremarkable. Of course Super Mario Bros. is a puzzle with a definite solution, it is obviously designed as a challenge to be overcome. The push towards more sophisticated and realistic graphical styles, though, makes the dissonance between the apparently naturalistic world and the providence affording constant progression more apparent, perhaps never more so than in The Last of Us, a world rendered with painstaking detail to evoke the feeling of exploring and surviving within the degraded ruins of civilization, yet every obstacle can be overcome using the handful of interactable objects in each room.

For all intents and purposes, to act within a game world is to do so with the implicit knowledge that it was made for you and that you can never make a mistake that cannot be corrected. This is why encountering glitches can sometimes be scary. Wandering truly out of bounds or falling through the world geometry, we recognize that we are no longer “in the hands of God” and are truly subject only to the forces of the simulation. Falling out of bounds can be endless, if the designers did not have the foresight to plan an out-of-bounds contingency (such as installing a kill plane).

So let’s play with this imperfect metaphor. Game developers are the gods of the game worlds that they create. Judeochrstian mythology has the creator God speak the world into existence with His words, and so too do game developers incant a sacred script (programming code) to speak the simulation into existence. Naught exists apart from that which they form with their words and numbers. They create worlds filled with inhabitants that “think” (in rudimentary ways) but are of unmistakably lower order and dignity than their creators by nature of belonging to a lower “reality” than that of their creators. If we want to be very cheeky with our metaphor, we could argue that the player-avatar is Jesus-like, possessing a confidence and conviction of a being who has entered the lesser reality from a higher one, possessing the knowledge of the “gods” but operating with the limited affordances of a subject within the pocket reality. The player-avatar even returns after death. But I write this comparison with my tongue firmly in my cheek; there is a better analogue for the player in this religious allegory.

Paradise Lost

INDIKA is a linear, narrative-based exploration-adventure game; what is often termed a walking simulator, though one that affords more agency and includes more action gameplay than most in the subgenre. The titular Indika is a nun serving in a small-town chapel in 19th century Russia. She is a humble and dutiful attendant but is widely disliked by other other nuns in her convent, presumably because of a history of aberrant behavior caused by what can be read as either psychosis (analogous to those depicted in the recently expanded Hellblade series) or the unwanted companionship of the Devil himself. Early in the game, we witness what we can only presume is a hallucinatory episode during a religious ritual, in which Indika witnesses a small man, accompanied by an unusually modern-sounding score of rock electronic music, crawl from the mouth of one of the other nuns and dance around. Indika recoils, disrupting the ceremony. The reaction of the other nuns indicates that this is not the first time such a disruption has occurred. They soon send her on an errand to deliver a letter. It is unclear whether the nuns are simply sending her away to afford themselves some peace in the absence of the nuisance Indika or whether they knowingly put her in harm’s way, knowing she must cross several lines of conflict during an active revolutionary conflict.

On her journey, Indika is accompanied by the voice of the Devil. He is rarely antagonistic towards her; rather, he comes across like a demanding audience, pushing Indika towards actions that would make for (what he expects might be) a more exciting story. He pushes her towards revealing her location when hiding from a dangerous attacker. He encourages her to spy upon those in illicit positions. He prods her towards romance with the male travel companion she takes partway into her adventure. He only becomes actively hostile, berating and belittling Indika, when she becomes lost or stuck, and this attack ends up becoming a necessary, world-altering force to work her way out of these predicaments.

Like many great Devil stories before, it is never clear whether she is truly being spoken to by an actual, spiritual adversary or whether the voice of the Devil is manufactured within her own mind. Certainly, she is strained by cognitive dissonance. The life of religious servitude is not one that she chose but is rather one she fell into out of necessity after running away from past sins. She seems to believe in God and the power of religious ceremony, but it’s unclear to what degree this is a natural belief that she has always held versus her adopting the necessary perspective to survive her vocation.

Where INDIKA shines is in its clever utilization of the video game format to message its religious themes. Though Indika, herself, struggles with her faith, we as players know that she does exist in a world created and maintained by gods (the game developers), and she is being invisibly led on a journey chosen and facilitated by those gods. In this sense, her faith is inarguably not misplaced. This is reinforced constantly with Uncharted or The Last of Us-style puzzles in which the path forward in her (linear) journey is interrupted by an obstacle that can be trivially overcome through the utilization of the objects immediately at hand. God is literally blessing Indika on her adventure with everything she needs to succeed.

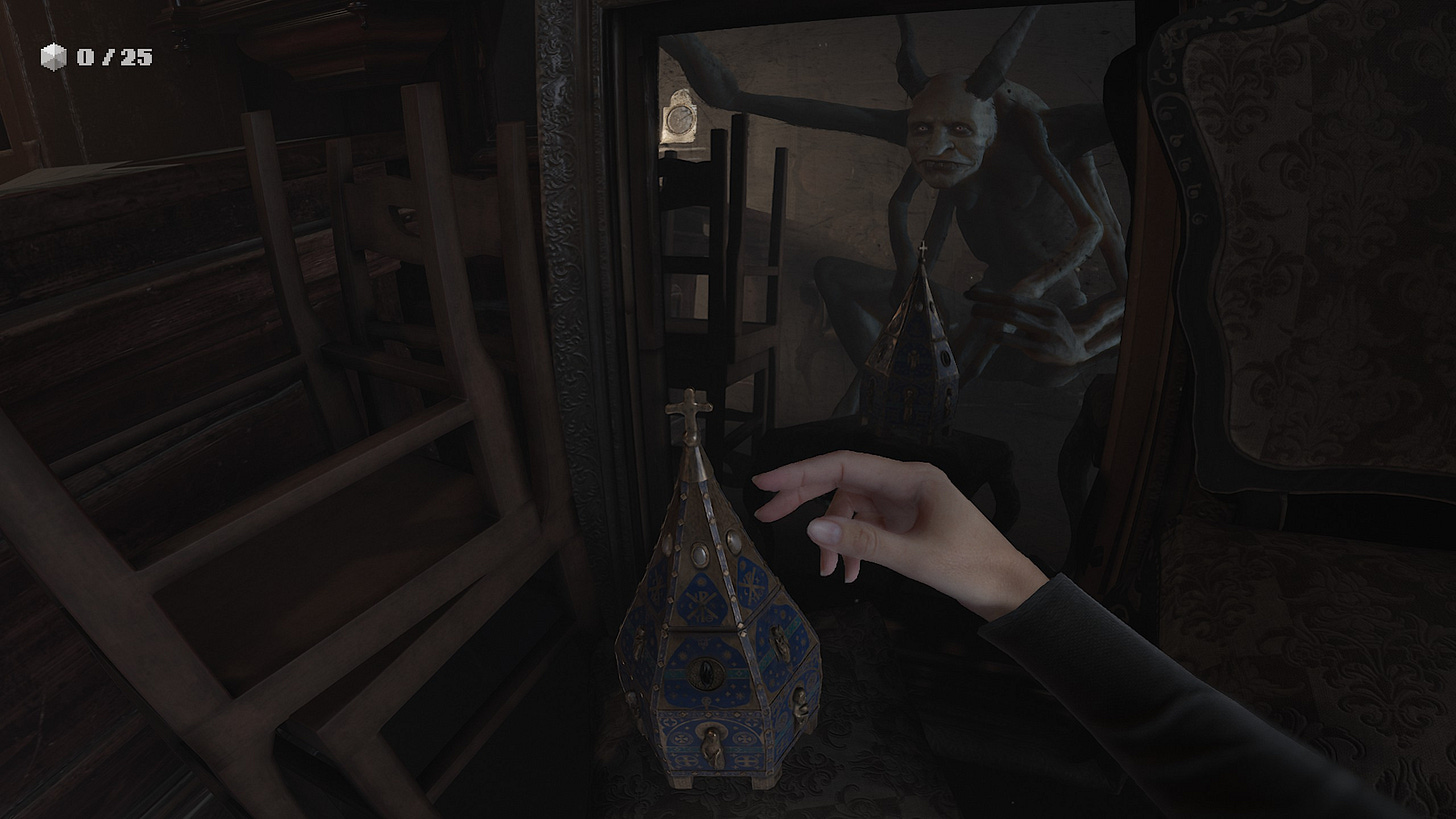

The game takes the metaphor further. If the game developers are God, the (nondiegetic) video games of the past are like religious texts. The game intelligently utilizes the visual language of arcade games to represent Indika’s faith. Interaction with religious artifacts (scattered throughout the game world as collectibles) are rewarded with floating coins, rendered in chunky pixels discordant with the otherwise naturalistic presentation of the game’s beautifully-rendered Unreal Engine 4 world. Those coins are used to “level up” Indika’s religious devotions, granting bonuses disguised as virtues, such as humility and piousness. The game even explicitly tells us that seeking collectibles and leveling up is useless; indeed, it does not feed back into the gameplay systems apart from multipliers that make further leveling up faster. Indika never becomes more diegetically capable; she only deepens her internal devotion, and she does it through an interface drenched in influence from early arcade games, artifacts from the world of the gods.

As mentioned previously, the influence and artifacts of the gods are not the only otherworldly discontinuity in Indika’s journey. She hears the voice of the Devil, and scenes of greatest Satanic influence are underscored by unmistakably modern rock-electronic music. If the developers are God, indicated as such by the evidence of artifacts originating from our world, outside of INDIKA’s diegesis, the game seems to assert that the Devil is representative of the influence of the player. This is a reasonable metaphor regardless of how you read the Devil’s presence within the story — as an actual, spiritual force (the player and the developers are both beings that supersede the level of reality of INDIKA’s world) or as a voice in her head caused by psychosis (the player’s influence is literally a separate motivational force within Indika’s mind and body). The player pushes Indika toward adventure, toward romance, toward action. The player is the demanding audience concerned with excitement and intrigue. The player is the one that who sees Indika not as a separate, living being but rather a tool worth only the entertainment that she can provide.

This framing implies an interesting dichotomy. If read from a religious (more specifically, Christian) perspective, this frames the player and developer as opposing forces. In a sense, this is true, in that the player’s role is to “knock over the dominoes” that the developers have set up. The developers create a world of potential possibilities and the player actualizes them into realized storytelling. The progress of a player through a linear story is a narrowing of narrative possibility, working toward the eventual ending in which every contingency has been decided and nothing is left to question any longer. However, just as easily, we could read the relationship between the developers and player as being cooperative. They work together to tell a story. Video game software does not become a story or, indeed, a work of art until it is enacted through live play. The player is not a source of destruction within the narrative, she is a fulfillment of the possibility space created by the developers for the purpose of play enactment.

This is analogous to the question raised by Milton’s Paradise Lost. Within the Christian mythology, God and the Devil are not equals in conflict with one another. The Devil cannot overcome God. In fact, the Devil is necessary to the process of the corruption and redemption of humanity (in the Christian framing, a redeemed humanity is greater than a blameless humanity, thus the Original Sin was a necessary step in the series of events that culminated in the death of Christ). It is the Judas Iscariot question; did he do wrong by betraying Jesus, or did he play a necessary part in fulfilling a prophesy set out by God? If the latter, can we truly ascribe moral judgment to his action? Did he act with true agency?

The interplay between God and Devil, between developer and player, comes to a head during a handful of “psychotic breaks” Indika experiences over the course of her adventure. These are narratively framed in terms of expressions of guilt (again, equally justifiable whether the Devil is read as a spiritual or hallucinatory presence). After Indika performs a sinful action, the Devil gloats over her, and the landscape literally cracks atwain around her. She can “restore her faith” through concentrated prayer, repairing the landscape for as long as the player holds the left trigger. In practice, this is a dual-state world, and the player must use and switch between both states to solve navigational puzzles (think Soul Reaver or that incredible time-traveling level in Titanfall 2). To solve these puzzles, Indika must reconcile both chaos and order, God and the Devil. In fact, these puzzles are not “breaks” in reality; they are designed puzzles — the realm of God within our metaphor. A thumb on the scale towards the Paradise Lost interpretation.

Taking stock of our complicated metaphor so far: Indika is a being within an intelligently-created world; a lesser sub-reality created by gods (game developers) that exist in the higher reality (our world). Religion (the seeking of divinity) within Indika’s world is visually framed in terms of artifacts of game design (classic arcade aesthetics and a level-up system). Indika is “haunted” by the influence of the Devil (the player) who motivates her toward adventure. The Devil-player is fearless because he operates with the knowledge of God-developer. Indika does not know she is in a world designed to facilitate her adventure, but the Devil-player does. The Devil-player exploits the instrumental providence of the God-developer in order to produce narrative catharsis, a selfish end ambivalent to the personhood of Indika.

Revelation

The religious metaphor comes to a head in the final act of the game. Indika and her companion spend the latter half of the game pursuing a particular religious artifact, hoping that its power will solve both of their problems. Throughout the game, Indika’s faith is tested and her belief in God comes into question. As an outside observer, this seems silly. She is literally being guided along a path directly toward her goal. She is prevented from straying from her pilgrim’s progress by literal walls and obstructions. Even for an exploration-adventure game, the hand of the God-developer can be plainly felt. But from the subjective perspective of Indika, subject within the game world, she does not see and does not recognize this guiding force, or what she sees, she recognizes as not being for her benefit.

In a late-game puzzle, she literally sees herself as a demon in a recursive, physics-bending obstacle course. If the Devil represents the influence of the player, perhaps this vision represents her desire to escape the “destined” fate of her life, or perhaps she is beginning to identify to a greater degree with the alluring agency and freedom of the player rather than the controlling hand of God.

In one of the final scenes of the game, she is betrayed by a fellow religious leader, shattering her remaining faith. Extradiegetically, the player witnesses the RPG-like level indicator drain back to nil. This was explicitly foreshadowed during loading screens (“the points are meaningless”), but the player still has an innate reaction to this. We worked hard to find those relics; we expect reward for making that number go up and up throughout the adventure. Indeed, this can be read as a cruel commentary about religious devotion in general; if we are truly beings of lesser value and lesser reality than God, how can we be sure there is any obligation to reward religious devotion?

We can observe this tension at play in real-world religious texts. Romans 8:28 in the Christian Bible states, “And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are the called according to His purpose”. Does this mean that the struggles that Christians experience will ultimately work toward their benefit (a question that becomes quite pointed when discussing martyrdom), or do individual struggles work toward the advancement of the kingdom of God, generally? One suffers so that God’s purposes advance. The goodness read into the latter statement hinges upon the reader’s trust in the purposes and intentions of God. Are martyrs asked to lay down their lives for the benefit of someone ultimately ambivalent to them?

The final twist of the knife comes in the game’s final action — the most aggressive indictment of religious ritual. Indika recovers the religious artifact from a pawn shop where it was thoughtlessly offloaded. She collapses to the floor, holding the artifact in her arms, in full view of a mirror in which she sees herself, again, as a demonic figure. In this moment, the player can shake the artifact, and oh do the points roll in! Coins upon chunky pixel coins spring out of the artifact with celebratory spectacle. The player can pause to be issued to the level-up screen, where the player can gain level after level after level, regaining and surpassing the systematized markers of devotion that Indika had recently lost. The numbers go up so pleasingly. Level ups grant multipliers. The numbers ascend ever faster. We can sit there, shaking the artifact and being rewarded with coins for as long as we wish.

This is a clear experiential demonstration of the fetishism of religious ritual. In this moment, the game calls upon another ludic parallel, the “clicker” game (also known as “idle” game in a delicious bit of semantic parallel). We love to see the points increase because we are conditioned to react positively from arcade games. We love to level-up because that reaction is conditioned from our history of playing RPGs. We feel the grip and pull of our conditioning from other video games driving an exercise we know to be meaningless. And, of course, if video games are the religious objects (artifacts of the gods) within our ludic metaphor, this parallels Indika’s desperate fetishism of the artifact in her hand as being a conditioned response from the religious teachings in her life. The system is shown to be self-perpetuating and ultimately useless; destructive, even, for the ritualistic shaking of the artifact wastes not only her time but our own.

Once the player has had enough of the endorphin-artifact, we choose to set it down. At this point, I was curious what the game would have Indika choose to do. Her story did not reach a narrative resolution or proper catharsis, but if I had understood the metaphor correctly, there was only one thing that would have been right for Indika as a character. She had to make the choice to reject the security of God. Further, for her to emerge as a self-actualized being, she has to step away not only from the God-developer but also separate from the symbiotic relationship with the Devil-player. Her life cannot be scripted for the amusement and catharsis of the player. And that is exactly what happens. She runs out of the pawn shop, leaving the third-person camera behind. Her story is not finished, but our voyeuristic view into it is. Just as she fetishized the religious artifact in order to extract God’s power for her own fulfillment, we too fetishized her as a narrative object for our own ends.

I will never find out how Indika’s story concluded. But I’m glad she is free to determine her own destiny, even if it leaves my cathartic desire unfulfilled. INDIKA speaks powerfully and posits soul-wrenching ideas wordlessly through its systems structure and (to borrow Ian Bogost’s term) procedural rhetoric alone. It is a remarkably intelligent game, and I hope a prominent step along the path toward more sophisticated ludic storytelling.